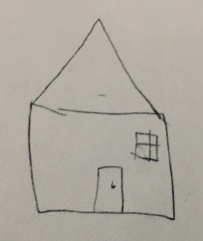

What happens when you ask people to “draw a house as if they were five?”

Last year I gave 19 talks, in the U.S. and Berlin, and asked more than 500 people just that. The results are in – and they are revealing:

the Primal Pattern-Embellished

the Primal Pattern

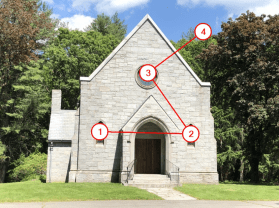

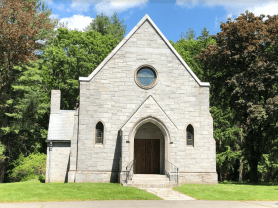

In 74% of the cases, people drew – with no direction on anyone’s part – a bilateral symmetrical building with two windows and a centrally placed door (see image above left) or a more embellished version of the same (at right). We call the first, ‘the Primal Pattern’ and the second, ‘the Primal Pattern-Embellished.’

the Primal Pattern-Reduced

In 22% of the cases we got a streamlined version, missing a door, or window(s), (see above) or occasionally all blank, or the ‘the Primal Pattern-Reduced.’

In only 4% of the cases did we get more unique interpretations; a floor plan, a room interior, in one instance, a castle.

Remarkably, the drawings varied little even if people were born or grew up outside North America or the U. S.; in fact, 32% of participants came from other continents (South America, Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia). Roof designs varied in some of these cases but not much else.

Turkey

Tanzania

Indonesia

So, why do people make such similar drawings? They can’t help it. The primal pattern, a version of the face, is in our DNA; it’s what we’re meant to see. Remember, we don’t see ‘reality,’ we see what nature wants us to ‘see’ based on our unique 3.8 billion-year-evolutionary trip; the process has preset the most important imprint for our lives.

“We are fundamentally social creatures – our brains are wired to foster working and playing together,” writes Bessel van der Kolk, MD, in The Body Keeps the Score (2014). And that’s just what the House Experiment demonstrates; everyone draws a face-like object because it’s the prime vehicle for human interaction and social engagement.

And why does this matter?

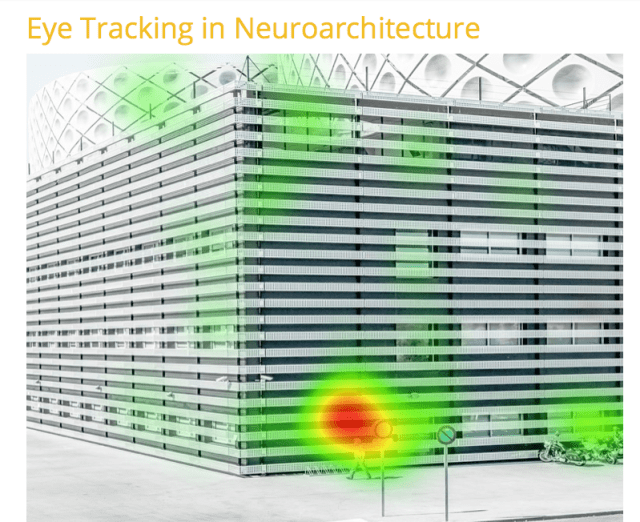

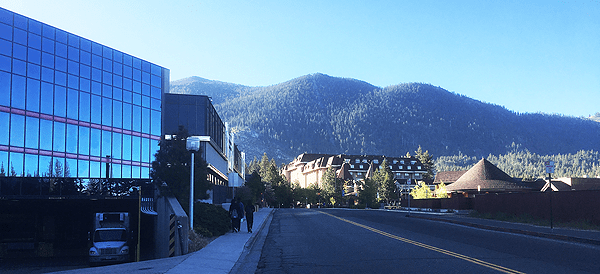

To build successfully for people: encouraging healthy communities, creating walkable byways, and promoting sustainable resource use, we need to recognize who we are and what we’re built to see. It can’t be any other way, actually. Streetscapes with primal patterning in their architecture will always be easier for us to walk down and feel at home in than ones without. Tracking primal patterning may even prove useful for understanding urban impact, and moving forward, building successful developments in the future.

After all, in the 21st century, isn’t it time to make Mother Nature proud?

Author: Ann Sussman

Editor: Janice M. Ward

Data analysis: Andrea Saunders, MSEE

For Tufts link see:

For Tufts link see:

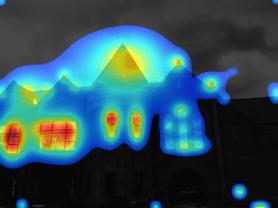

In 2ndPlace, Red Barn in West Acton, by Christopher Duncan shows the ‘regions’ which draw in the eye, and likelihood of doing so as a percentage (areas outside delineations are ignored); the original image is at right.

In 2ndPlace, Red Barn in West Acton, by Christopher Duncan shows the ‘regions’ which draw in the eye, and likelihood of doing so as a percentage (areas outside delineations are ignored); the original image is at right.