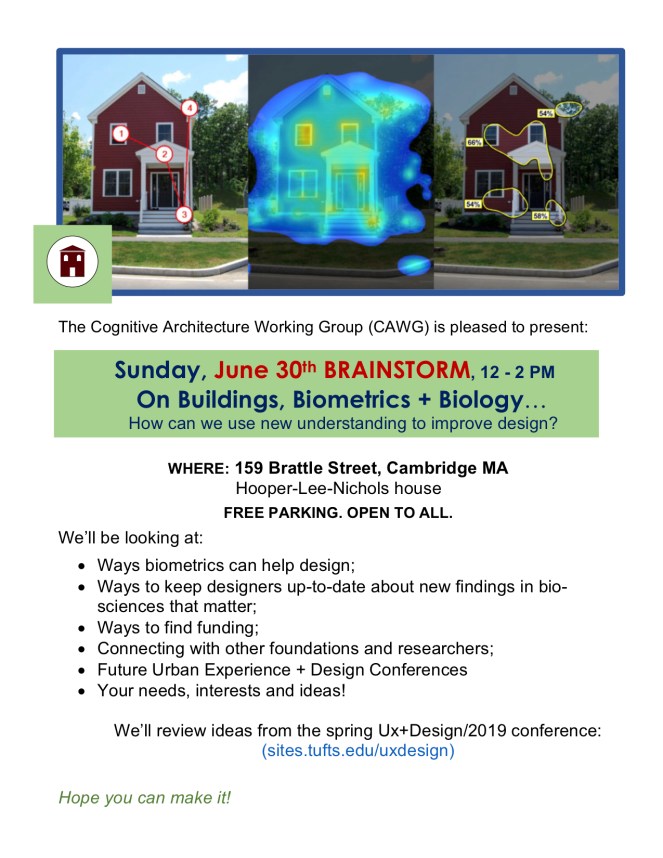

Here’s the info:

This event is free; we’ll be meeting in the Hooper-Lee-Nichols house, the second oldest in Cambridge, MA, just outside of Harvard Square at noon. Should be fun!

RSVP: annsmail4@gmail.com +/or heidi@pribell.com, if you can attend.

Here’s the info:

This event is free; we’ll be meeting in the Hooper-Lee-Nichols house, the second oldest in Cambridge, MA, just outside of Harvard Square at noon. Should be fun!

RSVP: annsmail4@gmail.com +/or heidi@pribell.com, if you can attend.

“Imagine there’s no autos

It’s easy if you try

Only healthy walking

And cycling ‘neath the sky”

—A riff on John Lennon’s, Imagine

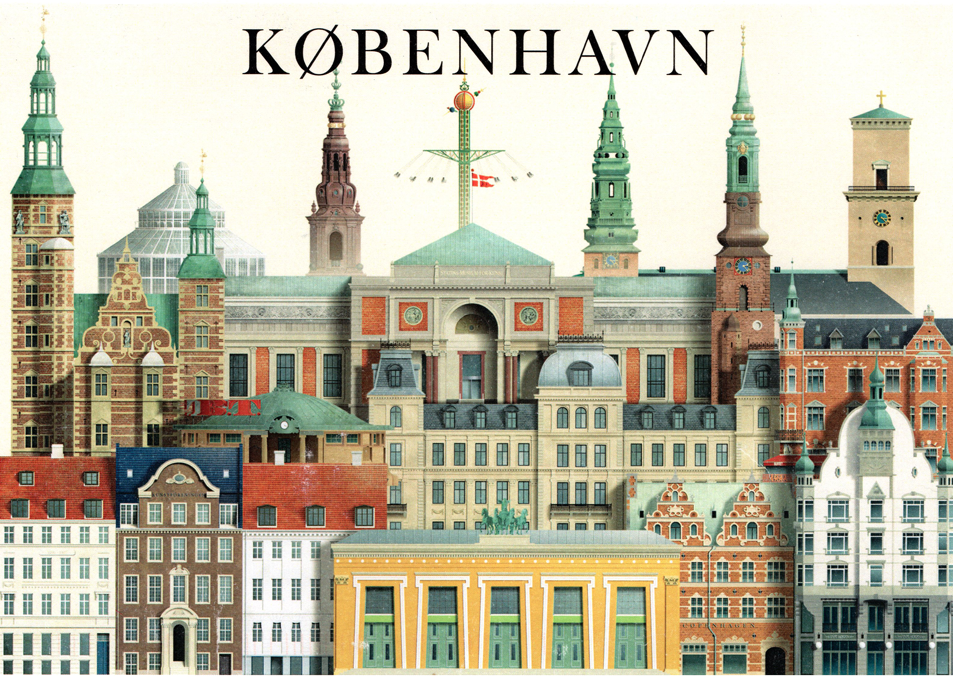

Visitors to Kyoto, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Porto and Paris don’t have to imagine – they already have miles of car-free streetscapes for walking, cycling and healthy living.

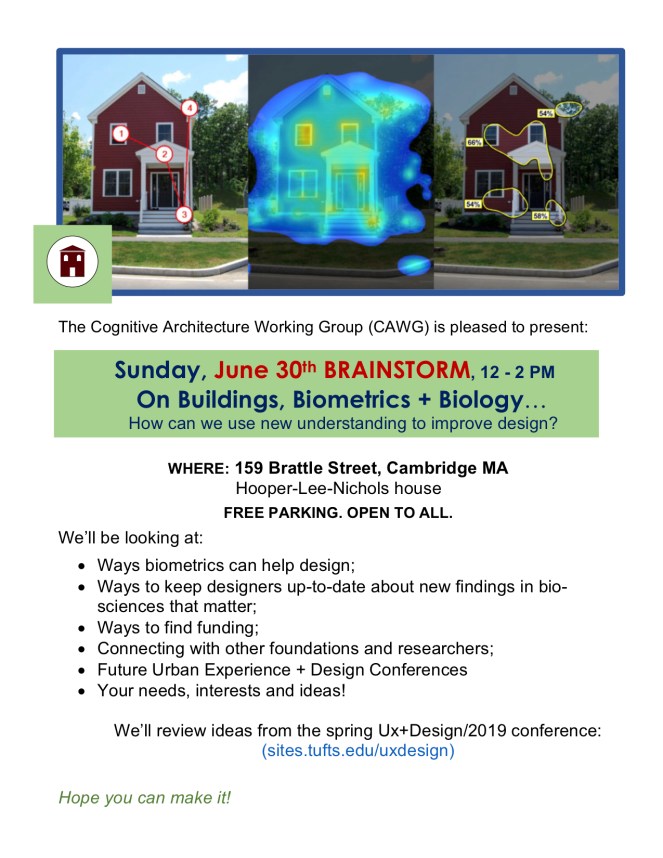

In Copenhagen, above, streets beckon, making you feel instantly welcome no matter your age, origin or native tongue. These streets speak ‘human’, saying you belong – even if you just arrived. Working to reduce car presence since the 60s, Denmark’s capitol also boasts 200 miles of bike lanes. And if Denmark leads the pack, other European cities get the message; in Paris and Stockholm central districts are car-less. Pedestrians are fine right in the middle of the road here – imagine! They aren’t relegated to crosswalks; they’re celebrated and since they don’t have to worry about relentless onslaught of autos, can think about other things! It’s so much easier to be a tourist in cities like these (see below) where walking’s made easy and delightful.

Amsterdam, in the Netherlands, voted this spring to remove 11,000 parking spaces from the Dutch capitol by 2025. These will be replaced by sidewalks, trees and more places for people to gather and enjoy life.

And the tendency to go car-free, is moving beyond Europe; a recent Business Insider article, “13 Cities that are Starting to Ban Cars” lists urban areas in Asia and South America embracing the trend.

Imagine this kind of living in the U.S. ? We’d have less stress, loneliness, greater longevity, reduced obesity and better health and well-being overall.

Imagine your town, your street, your way—without cars, just like in Porto, Portugal and Kyoto, Japan, (see below).

As John Lennon said:

“You may say I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one

I hope some day you’ll join us

And the world will be as one”

A good turnout at the 1st International Urban Experience and Design (Ux+Design/2019) conference at Tufts last month, which drew architects, planners, researchers and students from around the world interested in improving the built environment and better understanding our responses to it.

A good turnout at the 1st International Urban Experience and Design (Ux+Design/2019) conference at Tufts last month, which drew architects, planners, researchers and students from around the world interested in improving the built environment and better understanding our responses to it.

Here are some of the slides from the April 26th event, the ones below from the first panel: Using Biometrics to Measure Urban Design + Architecture.

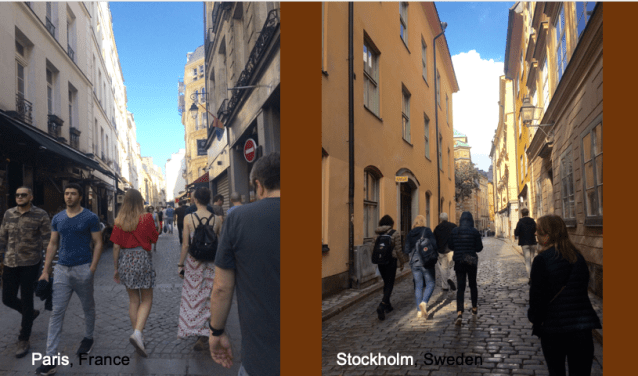

Presented with Peter Lowitt, FAICP, Director of the Devens Enterprise Commission. these slides* show how biometric aggregating software such as 3M’s web-based Visual Attention Software (VAS) can predict how people will take in a scene and forecast human behavior. Are we likely to walk down a street in a new development or choose to remain in the car?

The software, based on 30 years of eye-tracking studies, helps researchers explore how people ‘unconsciously’ take in their surroundings, predicting areas that immediately catch the eye. The ‘Regions of Interest’ that draw people in are shown below as percentages, with areas circled in red likely to attract the most attention, areas in yellow less so, and areas not-circled likely ignored completely.

These percentages track ‘unconscious’ brain behavior, or the first 3-to-5 seconds we look at something; this critical pre-attentive phase, before the conscious brain gets into the act, provides the foundation for behavior, we tend not to move towards something we haven’t fixated (or focused) on pre-attentively first.

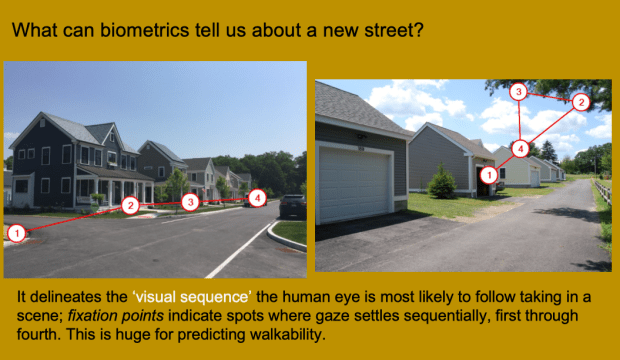

In the slide above we see how the arrangement of aligned porches, on the left, draws the eye down the streets, while the blank garages on a back alley, at right, do not. (And that happily, fits with the developer’s intent to encourage walk-ability on the main street and privacy around the garages.)

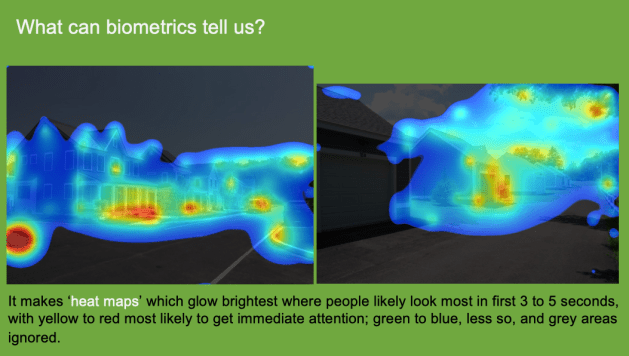

Biometrics are also great at create compelling images which, aggregating a lot of data, make the science accessible; in the case of the heat maps below, the images glow reddest where people look most, fading to blue in areas that receive less attention, and going black where likely no attention will be paid at all. It’s hard not to get it when things are presented this way!

What else can biometrics do? Predict the sequence and direction where we’ll not only look but likely walk! Fact is, walking bipedally is hugely complex for the human brain – so we do it best without having to consciously think about it! Below, with the visual sequence deconstructed, we see why the street at left will always invite walk-ability while the alley at right can’t; it’s simply too much for the brain to figure out, pre-attentively.

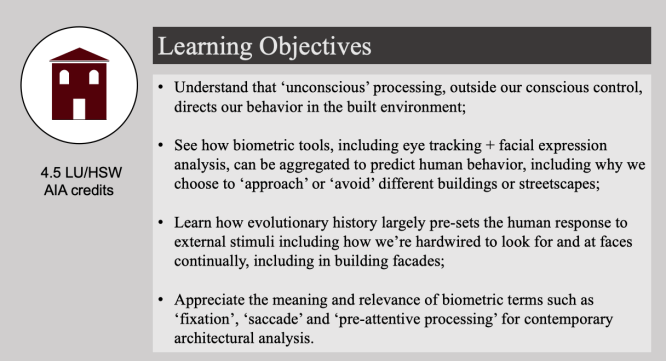

This all goes to show how ‘unconscious’ processing directs behavior in the built environment more than we may realize, which also was one of the themes (and Learning Objectives) of the Ux+Design/2019 conference. Others are listed below and we’ll return to them in future posts:

Stay tuned!

– – – – –

* the slides reference: “Seeing the Unseen in Devens: A Biometric Pilot Study to Better Understand the ‘Unconscious’ Human Experience” by Justin Hollander, PhD, Ann Sussman, R.A, Hanna Carr, Tufts ’20

Thanks to the attendees and presenters at Ux+Design/2019, the 1st International Conference on Urban Experience and Design on April 26 at Tufts University. This conference brought together creative thinkers from around the world who are shaping ‘evidence-based’ design practices, ones that embrace the hard data of our ‘unconscious’ responses to external stimuli.

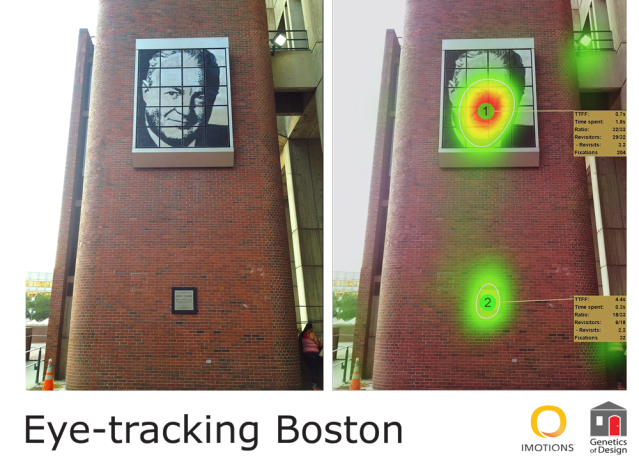

At the conference, we showed pictures of eye-tracked buildings in Boston and Somerville to show what really draws people to buildings and how our brains are set-up to take in their surroundings.

On display were photos like this of former Mayor John F. Collins (1960-1968), immortalized on the south side of Boston City Hall. The heat map (at right) glows brightest where people look most, showing how they head straight for the mayor’s face within 7/10’s of a second (TTFF or Time To First Fixation is 0.7s), and keep focusing on it in the seconds that follow – they simply can’t help it!

And, in Somerville, the photos below, of the view exiting the Davis Square T, show how people tend to focus on the building edge and tree at far right—not at all on the blank wall in front of them. Their behavior totally changes, however, if the building’s decorated with wonderful art, like the Matisse print below. Then, they can barely take their eyes off the structure.

Key takeaways from our conference were how ‘unconscious’ processing, outside of our awareness, directs behavior in the built environment—and that includes how our eyes move when first presented with new stimuli. We demonstrated how biometric tools, such as eye tracking, can predict behavior—determining how we ‘approach’ or ‘avoid’ architecture without ever thinking about it. The blank wall greeting transit riders exiting Davis Square station, for instance, is ‘avoidant’ and always will be (unless it’s painted with great art!). And as for Boston City Hall? The mayor’s face, at least, if not the architecture, is totally approachable.

For more information on the Ux+Design conference, click here.

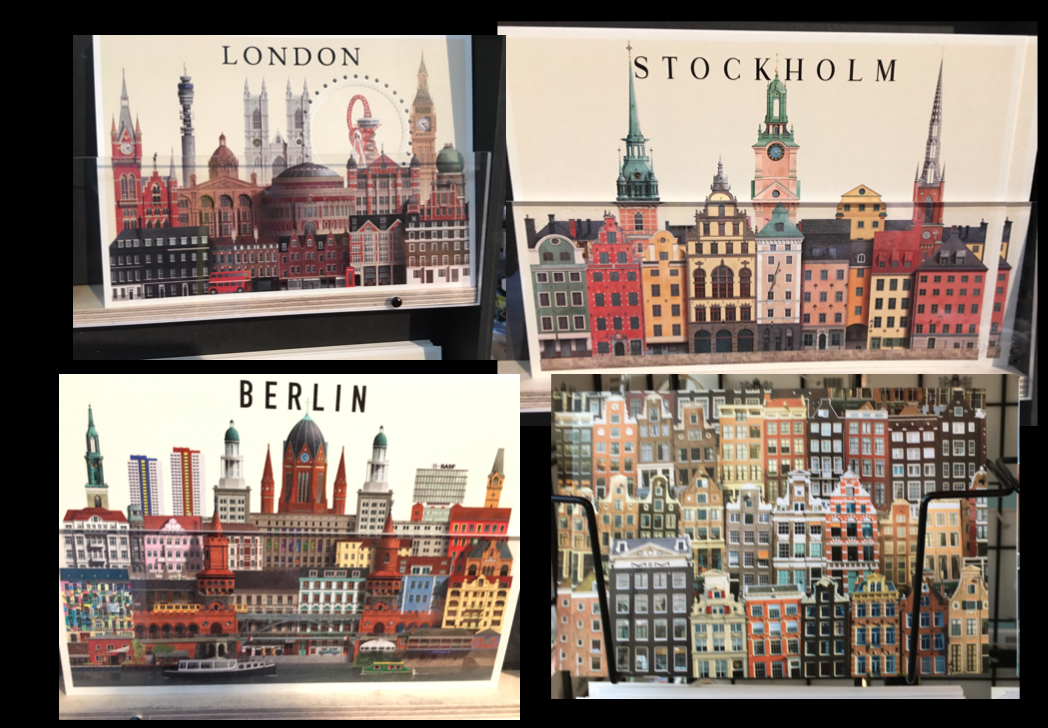

If you want to know which buildings attract people in cities—head to the postcard rack. The postcard above is from Copenhagen by Danish illustrator, Martin Schwartz, who’s created a series that capture “the soul of a city in a single print.” The cards below are for sale in Amsterdam:

If you want to know which buildings attract people in cities—head to the postcard rack. The postcard above is from Copenhagen by Danish illustrator, Martin Schwartz, who’s created a series that capture “the soul of a city in a single print.” The cards below are for sale in Amsterdam:

And these are on the racks at the Harvard Coop, Cambridge, MA, USA:

Note how rarely modern buildings appear—save in the distance, if at all. And what’s for sale, remarkably enough, seems curiously similar: pictures of older bilaterally-symmetrical buildings, with punched windows, distinctive top-middle-and-bottom arrangements and some color and carefully articulated details. Doesn’t seem to matter where you are—the postcards look curiously similar!

How can this be?

A postcard test can be seen as a kind of preference test—without the time and expense of actually setting up a user experience study. It shows what people like to see, and what appeals to them quickly enough they’ll actually reach out and buy it! Postcard sellers around the world can’t afford to create postcards no one buys—so they don’t.

And while the postcards obviously celebrate specific places, they also reflect something else significant and overlooked: who we are and what our internal brain architecture is set up to take in effortlessly.

One explanation for why the postcard test produces similar results around the world is because the same brain, or very similar brains, look at them: that of a bi-pedal mammal that delights in taking in diverse bi-laterally symmetrical shapes with distinct top, middle, bottom arrangements.

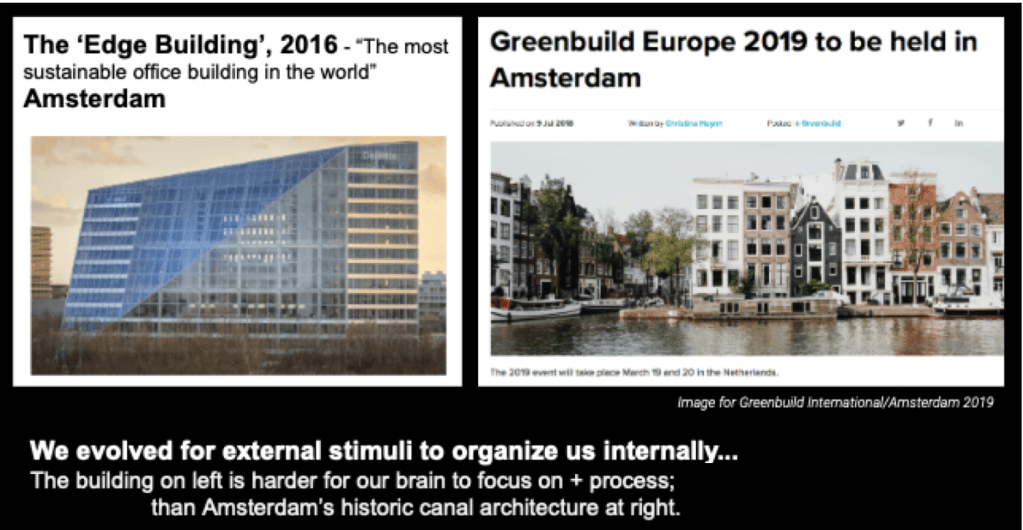

What’s also intriguing about the postcard test is that international travel and conference organizers appear to follow its results. They know that people aren’t likely to consider going to places that don’t please the eye instantly.

So, no surprise that a recent International Greenbuild/Europe conference held in Amsterdam* featured centuries-old canal architecture on its web page (see the photo below right) and not a modern LEED green-building or the “Edge Building” (at left) although it’s labeled the most ‘sustainable’ on the planet, and is also in the Dutch capital.

Who would want to head to the glassy techno-wonder at left, when the charming canal buildings beckon so much more effortlessly? They are easier to look at than the glass structure.

It’s all more evidence of how we are a biological and emotional species— not merely a logical one; something more architects, green builders and community designers would do well to consider when they plan our future habitat. First step, head for the postcard rack, or reach out to a postcard designer.

Fact is evolution’s real and quirky; to build the best future for us and other life on the planet, we’d do well to accept it.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

*Bottom three slides from ‘Hardwired Secrets of Sustainability: Why Feelings Matter so Much,’ Ann presented at Greenbuild/Europe in Amsterdam, March 20, 2019.

Genetics of Design is thrilled to co-sponsor the 1st International Urban Experience + Design/2019 conference with Tufts University, on April 26, 2019.

Genetics of Design is thrilled to co-sponsor the 1st International Urban Experience + Design/2019 conference with Tufts University, on April 26, 2019.

This all-day event in Medford, Massachusetts, will bring together architects, planners and researchers from around the world interested in improving the public realm and using new technologies and understandings from neuroscience to do so.

The conference is free for students and young practitioners, a nominal fee ($20) for all others; register here. Architects may receive 4.5 LU/HSW AIA credits for attending.

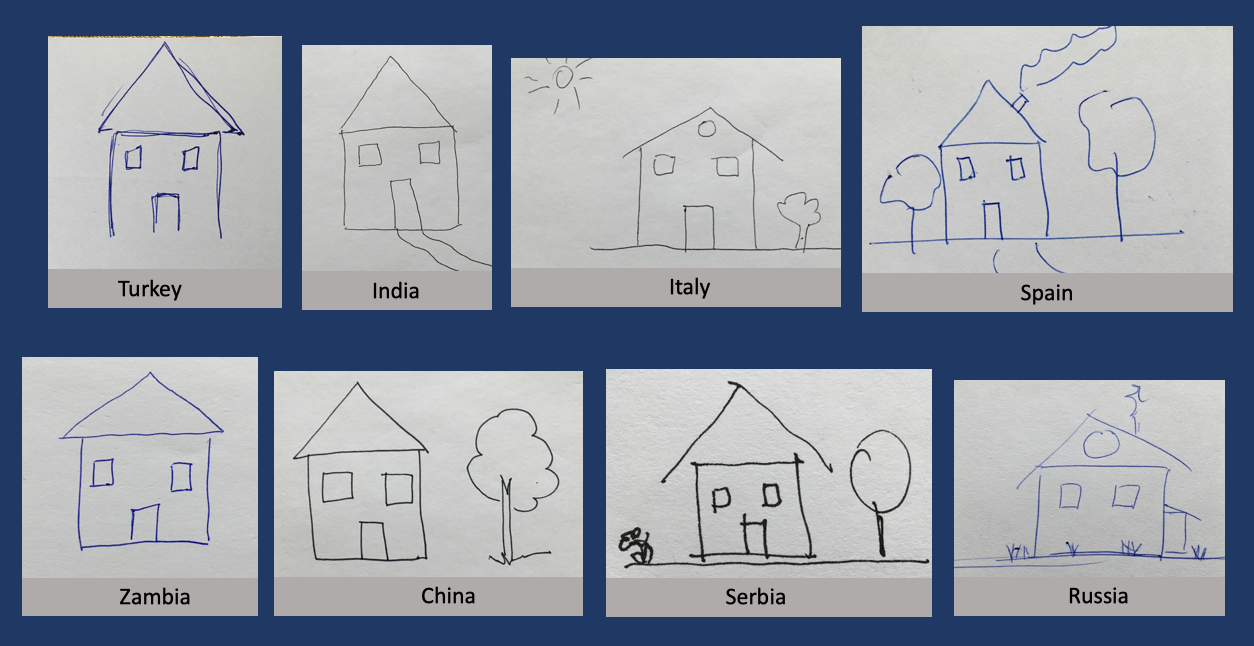

What connects us to other people? One commonality: we share an evolutionary path that gave us very similar internal templates. That’s what the ‘House Experiment’ demonstrates so well. Asked to “draw a house as if they’re five years old,” people draw almost identical images, without looking at anyone else’s work, no matter where they come from. The drawings above are by eight people, born and/or raised in eight different countries on three different continents.

What connects us to other people? One commonality: we share an evolutionary path that gave us very similar internal templates. That’s what the ‘House Experiment’ demonstrates so well. Asked to “draw a house as if they’re five years old,” people draw almost identical images, without looking at anyone else’s work, no matter where they come from. The drawings above are by eight people, born and/or raised in eight different countries on three different continents.

Cultural preferences sometimes creep in, such as in the house above, by someone from Morocco, Northern Africa – but, most often they do not. In fact, it’s astonishing to see two people, at different events, coming from opposite sides of the planet, draw nearly identical houses, as below:

Cultural preferences sometimes creep in, such as in the house above, by someone from Morocco, Northern Africa – but, most often they do not. In fact, it’s astonishing to see two people, at different events, coming from opposite sides of the planet, draw nearly identical houses, as below:

How can this be? It goes to show that, no matter our background, we are more the same than we realize and what we most like to see, what most grabs our attention – is pre-set; a version of the face, the pre-eminent pattern for a social species’ development and survival.

So, no surprise then, to find the primal pattern happily greeting everyone at the busy International Terminal at JFK airport in NYC – fact is, not only is it what we all draw, it’s also, really, the only choice, worldwide, for drawing us all in.

……………….

……………….

For more on the “Primal Pattern”:

Thanks to archnewsnow.com for linking to this post.

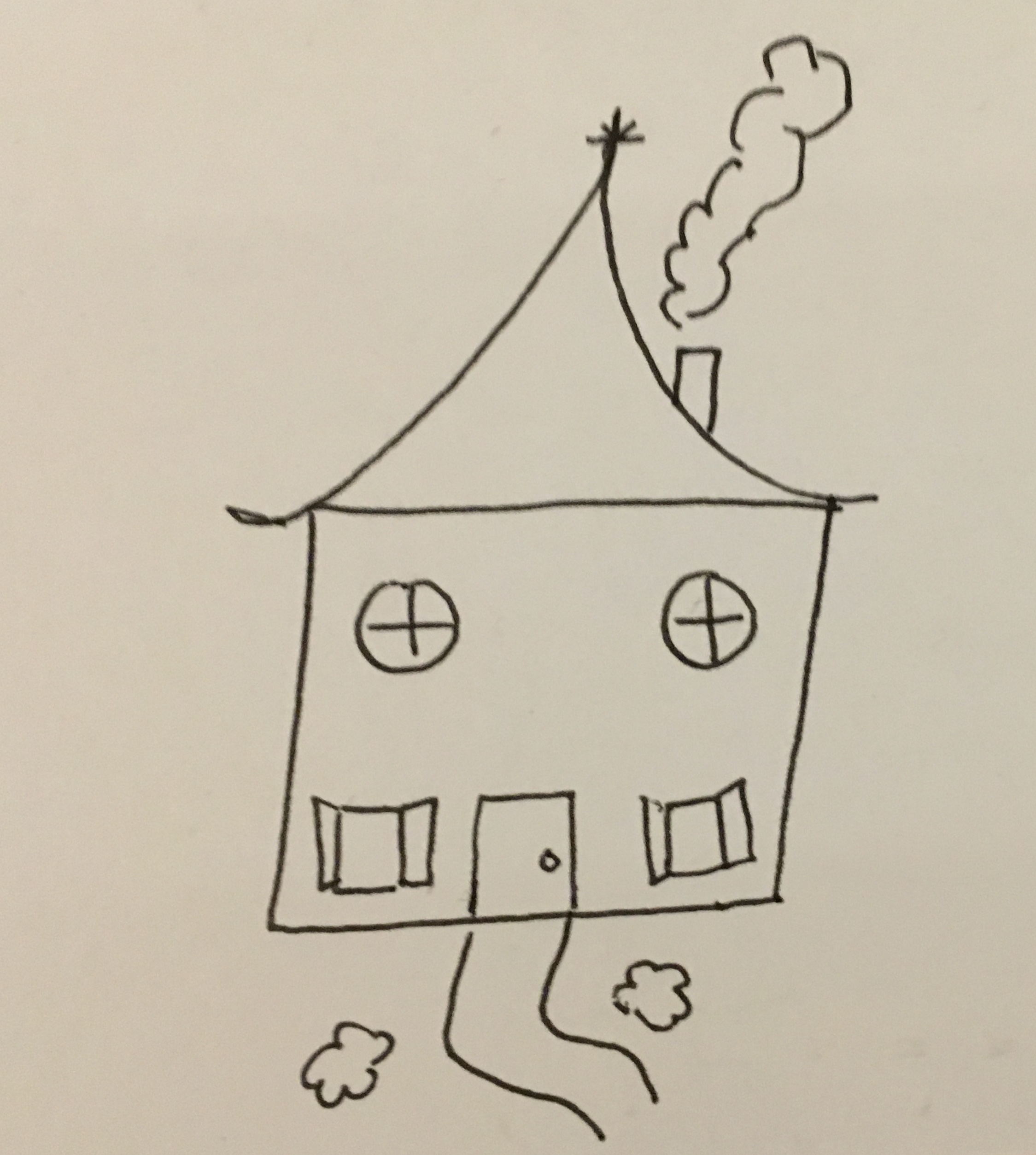

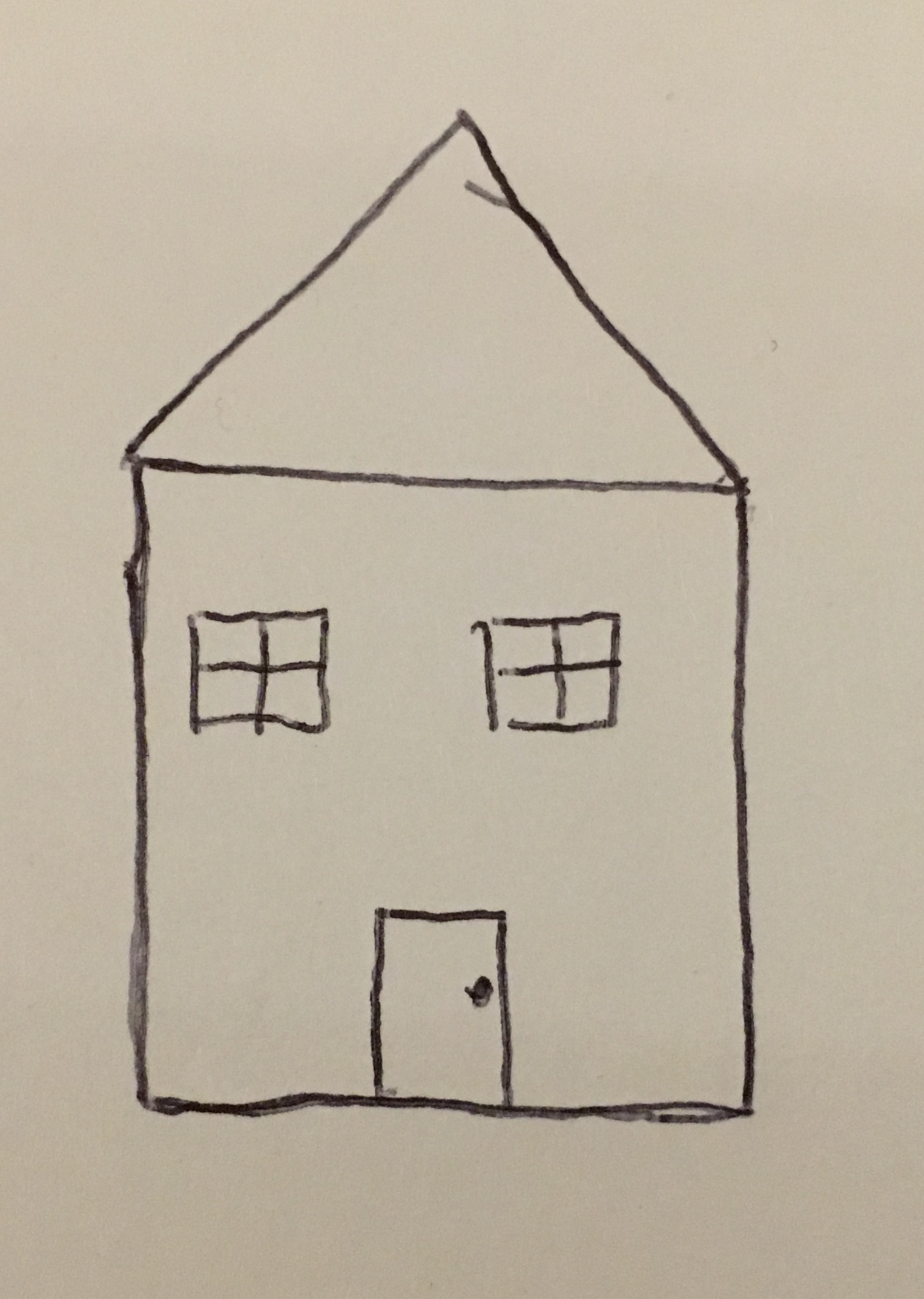

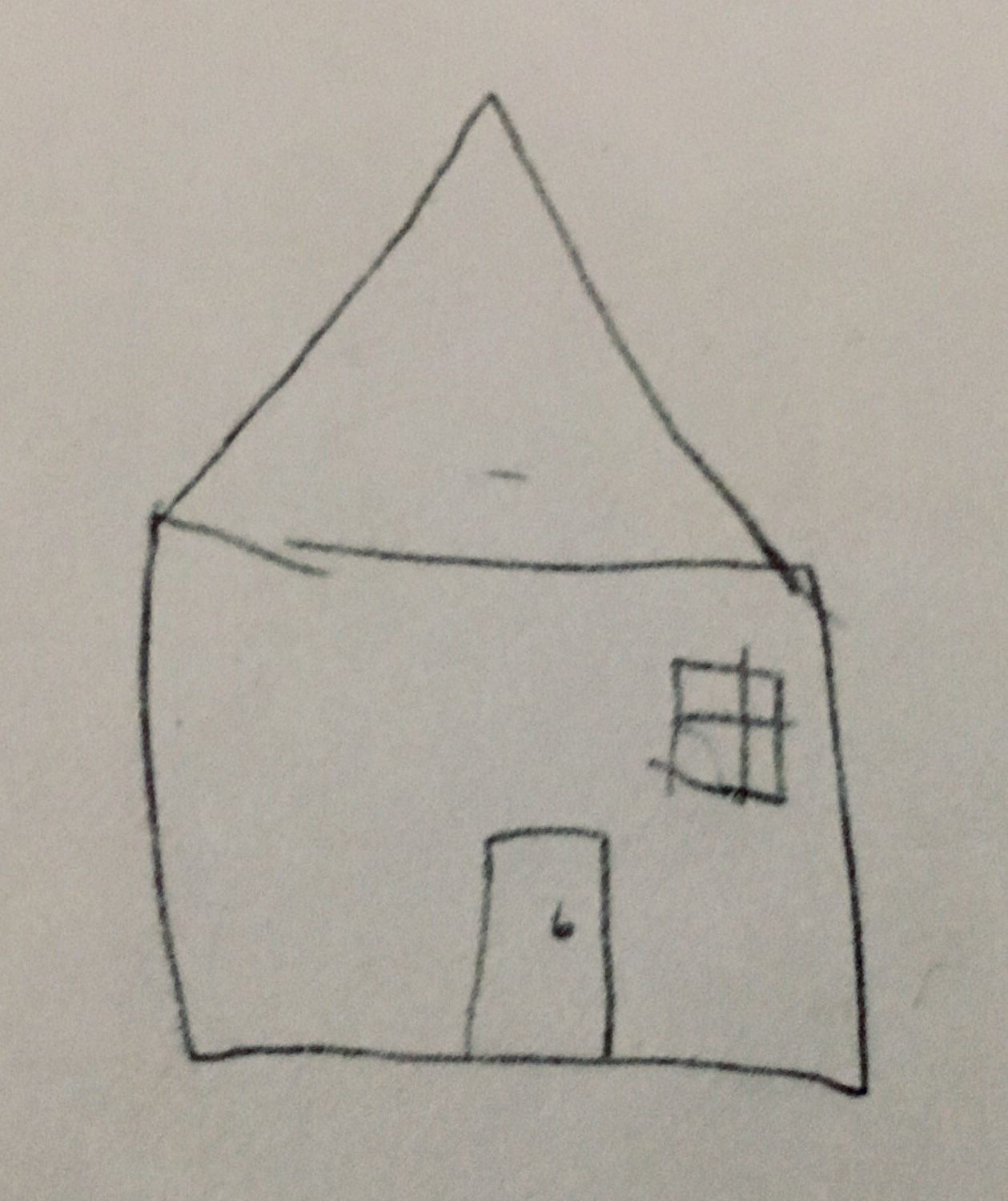

What happens when you ask people to “draw a house as if they were five?”

Last year I gave 19 talks, in the U.S. and Berlin, and asked more than 500 people just that. The results are in – and they are revealing:

the Primal Pattern-Embellished

the Primal Pattern

In 74% of the cases, people drew – with no direction on anyone’s part – a bilateral symmetrical building with two windows and a centrally placed door (see image above left) or a more embellished version of the same (at right). We call the first, ‘the Primal Pattern’ and the second, ‘the Primal Pattern-Embellished.’

the Primal Pattern-Reduced

In 22% of the cases we got a streamlined version, missing a door, or window(s), (see above) or occasionally all blank, or the ‘the Primal Pattern-Reduced.’

In only 4% of the cases did we get more unique interpretations; a floor plan, a room interior, in one instance, a castle.

Remarkably, the drawings varied little even if people were born or grew up outside North America or the U. S.; in fact, 32% of participants came from other continents (South America, Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia). Roof designs varied in some of these cases but not much else.

Turkey

Tanzania

Indonesia

So, why do people make such similar drawings? They can’t help it. The primal pattern, a version of the face, is in our DNA; it’s what we’re meant to see. Remember, we don’t see ‘reality,’ we see what nature wants us to ‘see’ based on our unique 3.8 billion-year-evolutionary trip; the process has preset the most important imprint for our lives.

“We are fundamentally social creatures – our brains are wired to foster working and playing together,” writes Bessel van der Kolk, MD, in The Body Keeps the Score (2014). And that’s just what the House Experiment demonstrates; everyone draws a face-like object because it’s the prime vehicle for human interaction and social engagement.

And why does this matter?

To build successfully for people: encouraging healthy communities, creating walkable byways, and promoting sustainable resource use, we need to recognize who we are and what we’re built to see. It can’t be any other way, actually. Streetscapes with primal patterning in their architecture will always be easier for us to walk down and feel at home in than ones without. Tracking primal patterning may even prove useful for understanding urban impact, and moving forward, building successful developments in the future.

After all, in the 21st century, isn’t it time to make Mother Nature proud?

Author: Ann Sussman

Editor: Janice M. Ward

Data analysis: Andrea Saunders, MSEE

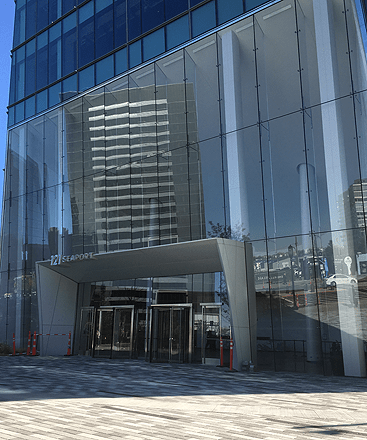

Sharp edges on the new, shiny glass tower at 121 Seaport, Boston, say, “You don’t matter.”

Maya got that right: people never forget how you make them feel. The same could be said of the buildings we live and work in. Who would want to enter the new glass box at left?

A recent BBC article describes The Hidden Ways That Architecture Affects Us—how “buildings and cities can affect our mood and well-being, and that specialized cells in the hippocampal region of our brains are attuned to the geometry and arrangement of spaces we inhabit.”

These scientific studies reveal that people embrace green spaces, patterns, colors and curves, while we shun sharp edges, blank facades and vast, unsheltered spaces. Buildings speak to us – wordlessly saying:

“Come stay with us.”

“I’m here for you,” or

“You don’t matter at all.”

And people respond accordingly, approaching or avoiding a place—or entire sections of a city.

On a recent trip to the Seaport District in Boston, we paid particular attention to the sentiments in the air, comparing the old and new blocks by the ocean.

Visit my space,” the old brick building on Summer Street said. |

“Stay away,” the Boston Convention Center told us. |

“Bring the kids,” boomed the antique Milk Bottle. |

“Enjoy my harbor view,” said the patio. |

And we came away with one certain conviction: the old blocks beckon much more than the shiny, new ones do.

We saw that buildings and blocks can be unforgettable depending on how they made us feel. And come to think of it, it can’t be any other way, of course, for like with people—how they make us feel is what really matters.

Author: Janice M. Ward,

Editor: Ann Sussman

Why does this matter? Well, turns out it’s huge if you care about building better places for people.

Evolution is real and fascinating; to build healthy sustainable places for people, designers need to look into it. Read more at Architectural Digest site: Why Architectural Education Needs to Embrace Evidence-Based Design, Now .

* Images made with 3M’s VAS software.

Where The Eagles Fly . . . . Art Science Poetry Music & Ideas

Knowledge transfer engineering

Cool stuff in construction

The Biology behind Design that Delights

A blog by Gehl Architects

The Biology behind Design that Delights

Style Wars: classicism vs. modernism