“I see a red door and I want it painted black”

– Mick Jagger & Keith Richards

Aside from the Rolling Stones desire to “Paint it Black,” most people are attracted to red doors. Not only is red a look-at-me color, red doors are important culturally, historically and, now, scientifically.

Aside from the Rolling Stones desire to “Paint it Black,” most people are attracted to red doors. Not only is red a look-at-me color, red doors are important culturally, historically and, now, scientifically.

Both the Red Door Spa and Talbot’s clothing chains use red doors as icons to attract customers. Red doors mean good luck to the Chinese, a paid-off mortgage to the Scotts, and a source of energy to Feng Shui followers.

Traditionally, red doors have represented safe havens. The Old Testament refers to a smear of red lamb’s blood placed above a doorway to offer protection for Israelite children against a plague coming to Egypt. In early America, a red door stood for welcome, a symbol of hospitality and a place to rest. During the American Civil War, red doors were rumored as refuges for travelers along the Underground Railroad.

The color red influences our behavior, says Scientific American; everything from your behaviour in the workplace to your love life, according to a BBC report on color psychology, the study of hues on human behavior. We associate red with extremes: love and hate, life and death—red hearts, blushing faces, scarlet letters, stop signs. Red activates our appetite so much that restaurants often use it on walls, table cloths, napkins, logos, menus and advertising.

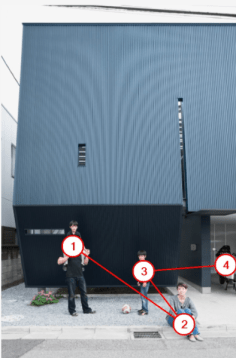

So the house with the red door in Figure 1 piqued our interest when we saw it in Dwell Magazine’s list of “10 Homes with Distinctive Facades.” Those facades purportedly make those homes memorable. And we wondered, would eye tracking support the color psychology? Does the facade or the color red make that home memorable?

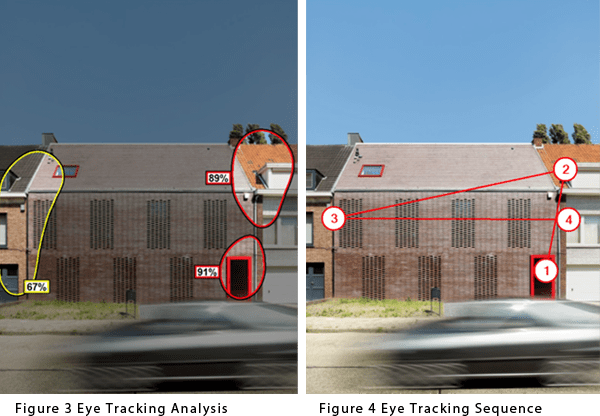

Using eye tracking software from 3M called VAS (Visual Attention Software) that predicts where people will look within the first 3 to 5 seconds of viewing a photo (before their conscious brain can react), we examined the Belgian house with the red door designed by dmvA architects. Figure 2 shows the eye tracking heat map of its façade. The red areas glow brightest where people likely look most.

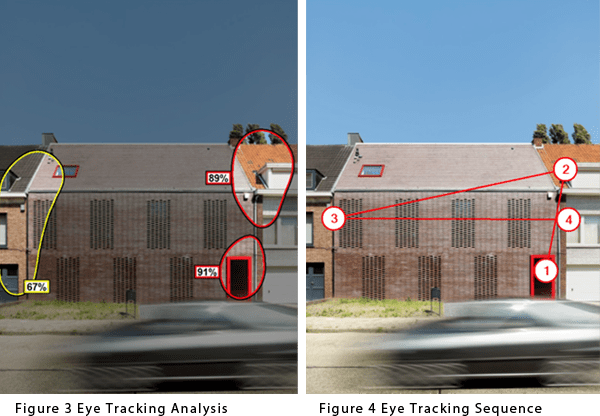

In Figure 3 the eye tracking analysis’ red outlines indicate a 92% probability of viewing attention directed at the red door, 89% at the neighbor’s red roof, and 67% at the contrasting edge of the house. The numbers in Figure 4 show the viewing sequence with the red door just where we’d expect: first.

We live “in a world dominated by images and colour. Our sense of vision largely dictates how we perceive the environment around us,” says an article in The Conversation, Making Sense of Evolution. And human vision, which is dependent on light reflection to the retina that allows us to see color, responds to red light most. The retina contains photoreceptors called cones; and about 64 % of cones respond to red light, about 33% to green light, and about 2 % to blue light. When light hits the cones, a signal is sent from the optic nerve to the visual cortex of the brain which processes the information.

The eye tracking results of the house with the red door show that only the red door was memorable because our brains (without our conscious control) look for the color red first, then the edges of the building.

So, if you want the front of your house to get noticed, don’t follow Mick’s advice. Instead, paint it red.

Here’s a question. In the photos above of two urban arcades, which one would you rather be in?

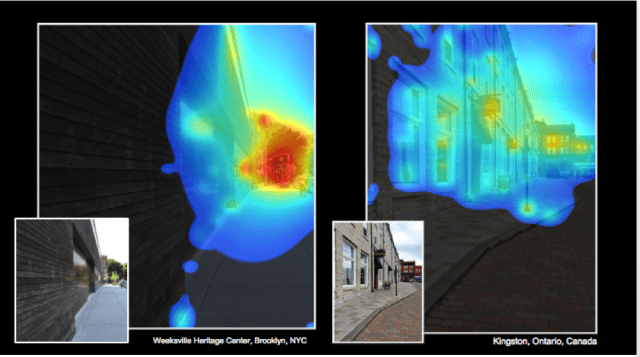

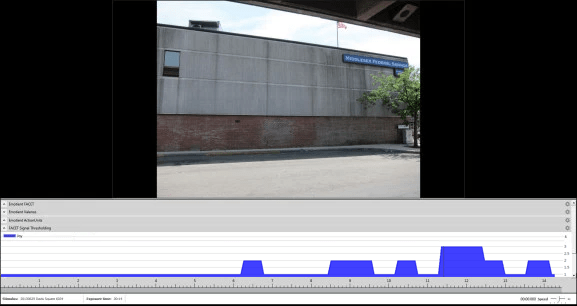

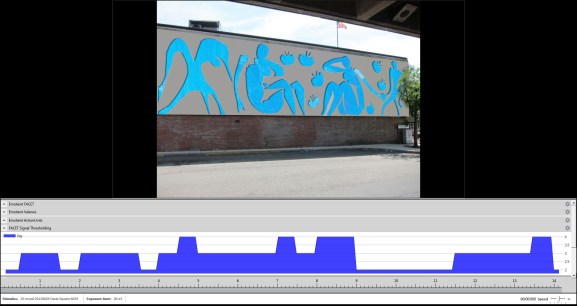

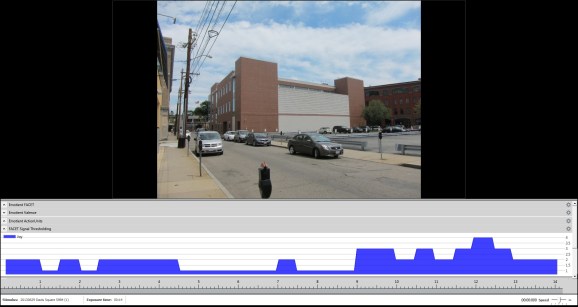

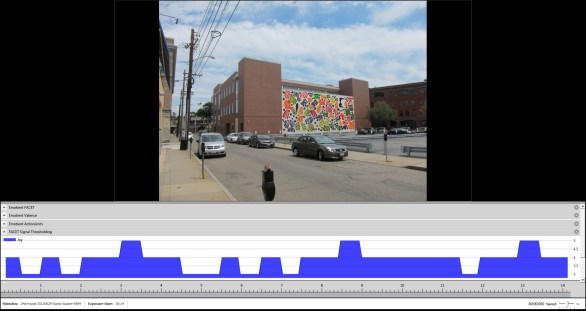

Here’s a question. In the photos above of two urban arcades, which one would you rather be in? Which street would you rather walk down? Both form part of historic centers, the one on the left in Brooklyn, NYC, the other, at right, in Ontario, Canada.

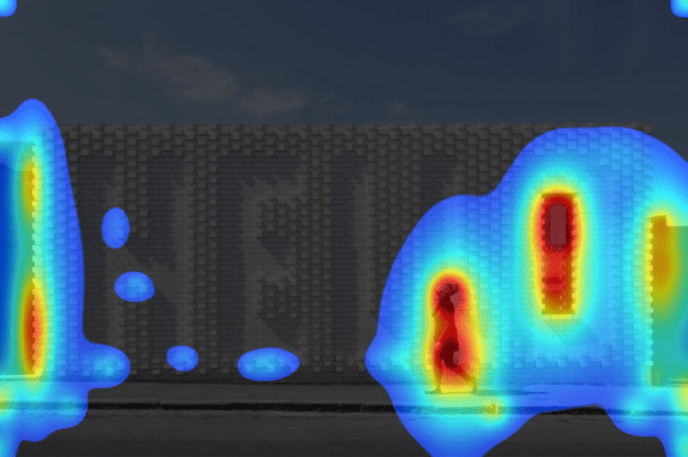

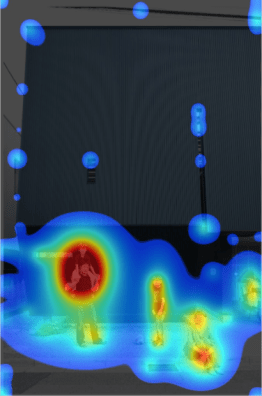

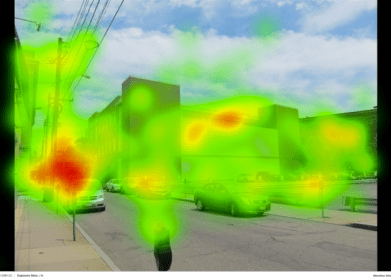

Which street would you rather walk down? Both form part of historic centers, the one on the left in Brooklyn, NYC, the other, at right, in Ontario, Canada. The ‘heat maps’ above glow brightest where people look instinctively, fading to black in areas ignored. The results suggest one reason the Brooklyn streetscape isn’t favored is our unconscious brain won’t let us look at it. And that’s huge because unconscious brain activity always lays the foundation for conscious behavior. It guides it. We don’t readily move towards or engage with a place our pre-attentive processing has determined is to be ignored.

The ‘heat maps’ above glow brightest where people look instinctively, fading to black in areas ignored. The results suggest one reason the Brooklyn streetscape isn’t favored is our unconscious brain won’t let us look at it. And that’s huge because unconscious brain activity always lays the foundation for conscious behavior. It guides it. We don’t readily move towards or engage with a place our pre-attentive processing has determined is to be ignored. Aside from the Rolling Stones desire to “Paint it Black,” most people are attracted to red doors. Not only is red a look-at-me color, red doors are important culturally, historically and, now, scientifically.

Aside from the Rolling Stones desire to “Paint it Black,” most people are attracted to red doors. Not only is red a look-at-me color, red doors are important culturally, historically and, now, scientifically.

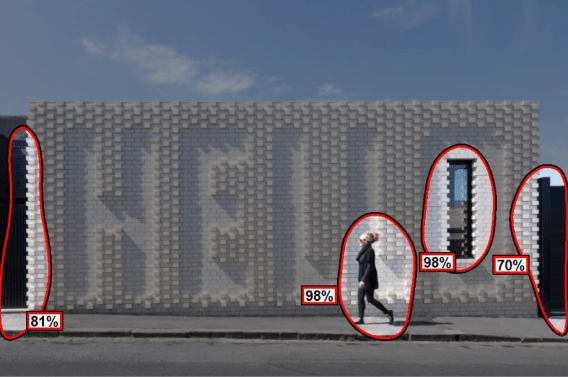

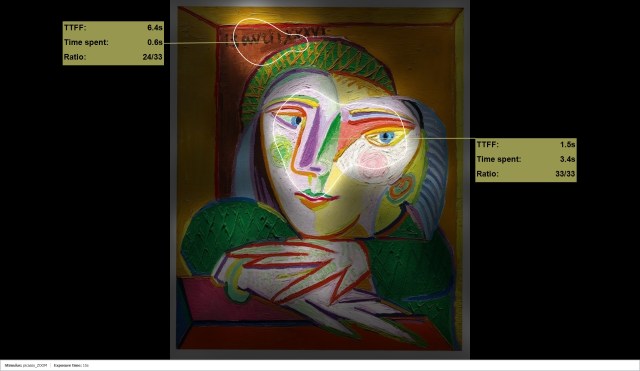

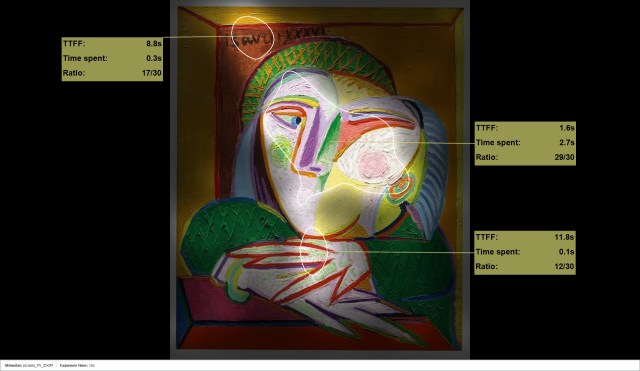

According to this analysis, there’s a 66% probability that people will look down the street, past the new art building; 64% chance they’ll look at the bright colors on the building opposite the art center – and 55% they’ll take in the sidewalk cone. The probability they’ll ignore the art museum itself is close to 100% since most of it’s in grey, falling outside the outlined regions.

According to this analysis, there’s a 66% probability that people will look down the street, past the new art building; 64% chance they’ll look at the bright colors on the building opposite the art center – and 55% they’ll take in the sidewalk cone. The probability they’ll ignore the art museum itself is close to 100% since most of it’s in grey, falling outside the outlined regions.

How did this happen? “Fixations drive exploration,” explains a cognitive scientist we know. The eye is hardwired to focus on specific objects in the environment; if it finds none the brain goes on alert – until it finds something to attach to. The mural provides a place for instant ‘pre-attentive’ (or unconscious) eye attachment, it fits what our brain wants to see and needs to see to emotionally regulate and move forward. The students immediately picked up on it; so did the 24 people in our pilot-study. It all makes sense, of couse, once you remember that as an evolutionary artifact, we see the world Mother Nature wants us to see in the way she wants us to see it – and she is no libertarian, but a control freak.

How did this happen? “Fixations drive exploration,” explains a cognitive scientist we know. The eye is hardwired to focus on specific objects in the environment; if it finds none the brain goes on alert – until it finds something to attach to. The mural provides a place for instant ‘pre-attentive’ (or unconscious) eye attachment, it fits what our brain wants to see and needs to see to emotionally regulate and move forward. The students immediately picked up on it; so did the 24 people in our pilot-study. It all makes sense, of couse, once you remember that as an evolutionary artifact, we see the world Mother Nature wants us to see in the way she wants us to see it – and she is no libertarian, but a control freak.

Uncovered in South Africa almost a century ago, and now in a museum there, the pebble is considered – at 3 million years old – the world’s oldest example of ‘symbolic thinking’, the ability to think in images and symbols which children develop in pre-school. This is the trait needed to create art and language, critical for the development of human society.

Uncovered in South Africa almost a century ago, and now in a museum there, the pebble is considered – at 3 million years old – the world’s oldest example of ‘symbolic thinking’, the ability to think in images and symbols which children develop in pre-school. This is the trait needed to create art and language, critical for the development of human society.