As a social species, we are built to see eyes, so we look for them all the time — everywhere — without conscious awareness or control. When we find them, they grab our attention, anchoring us in space, securing us to a place. So, it’s no surprise that tour buses driving through historic Cambridge, Massachusetts, always stop in front of the Harvard Lampoon building (below c.1909), home of the university’s satirical campus weekly. This building looks like it’s waiting to see you. How else to make a tourist trip memorable!

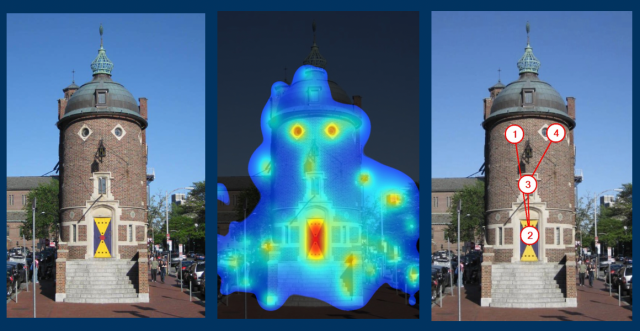

The Harvard Lampoon Building with VAS analysis ©geneticsofdesign.com; original image ©wikimedia

A quick assessment with biometric software, (3M VAS), predicts people return the favor, instantly focusing on its round-eye-like windows. Visual Attention Software, or VAS, predicts where people look ‘at-first-glance’, the first 3-to-5 seconds they take in a scene, and creates ‘heat maps’ that glow brightest where people look most, (central image above), and visual sequence diagrams, (above right), predicting the order they’ll likely look at things — showing again how much the eyes have it. (Yes, a mouth-like door gets attention too, but notice how VAS predicts our brain directs us to check out both of the ‘eyes’, ‘at-first-glance’, before conscious awareness kicks in.)

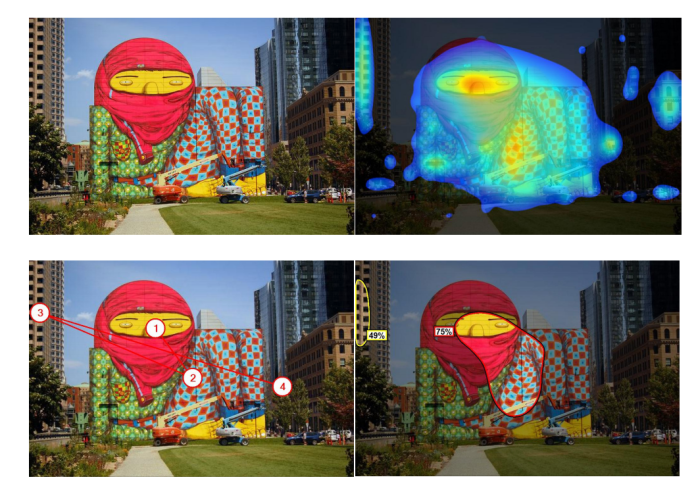

Greenway Mural with VAS analysis ©lingchuanmeng

The same holds true for murals on buildings like the one above, temporarily displayed on a blank wall in Boston’s Greenway, a few years ago. We see here how the heat map, at top right, glows brightest in the eye area while the red outlines of the ‘areas-of-interest’ diagram below it, show 75% of viewers instantly focus on the central part of the portrait which also might suggest an oval eye.

Face eye tracked with iMotions software ©geneticsofdesign.com

Photos of people show the eye bias too, with the ‘heat map’ on the face above created with iMotions eye-tracking software, in an on-screen 15-second testing interval. These eye-tracking studies also reveal something else important and too-often overlooked: how human perception is dyadic — it’s relational; we’re built to see each other and need to do so for survival including regulating our emotions on a daily basis. So, like breathing and eating, we arrive in the world hardwired to check out other faces all the time, everywhere, focusing on eyes to get the most critical information about our surroundings. And, from our brain’s million-year-old perspective, it does not matter if the ‘face’ in front of us is fake, or in an inanimate building facade, it’s going to check it out.

Why does this matter? Because to understand and build architecture successfully today, it’s important to acknowledge our ‘secret’ human biases that secured our survival over millennia. A famous line from William Faulkner comes to mind:

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Remember that saying if you want to understand how people really ‘see’ architecture, and what people still need to see and feel to be at their best, today. We are not modern and evolution has preset the way we look out on the world and what we most need to see. The eyes have it.

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Thanks to Lingchuan Meng, Boston Architectural College (BAC) B.Arch. candidate, and a student in Architecture & Cognition, 2018, class, for the VAS images of the Greenway mural.

Thanks to The Greenway Conservancy, News for linking to this post, November 13, 2019.

Thanks to ArchNewsNow.com for linking to this post, November 14, 2019.

Thanks to CNU (Congress for the New Urbanism) Public Square blog for publishing this post, November 18, 2019.

Pingback: Why Buildings Need Eyes | Beauty, Neuroscience & Architecture

Pingback: Empathy in Design: Measuring How Faces Make Places | The Genetics of Design