“First life, then spaces, then buildings–the other way around never works.” Jan Gehl

While Boston celebrated the start of the American Revolution on Patriot’s Day this week, the city of Somerville, two miles west, started a different kind of rebellion without firing a shot.

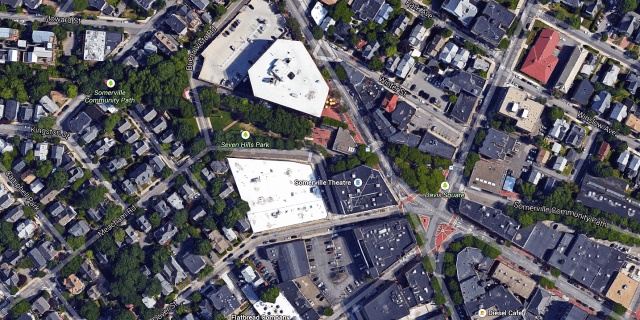

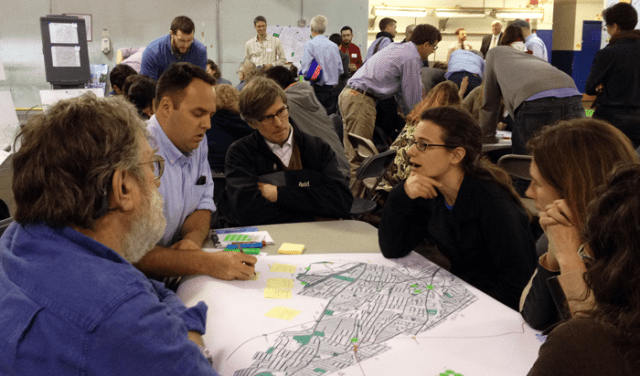

Somerville, the densest city in the Northeast with 75,000 residents in four square miles, held a historic public meeting called ‘People First Design Workshop.’ The goal: transform city planning by putting human habits and concern for their well-being at the center of the process.

The method? Use the game-changing techniques from Gehl Architects, the Danish firm that turned Copenhagen into the most walkable, bikeable city on earth where 50% of residents cycle to work and “many middle class families with kids don’t even own a car,” according to government reports. The Danish capital’s earned the ‘most livable city in the world’ award the past two years running.

“Who are you designing for… people or cars?” asked Jeff Risom, Partner and Director of Gehl Studio, the US branch of the firm, at the April 21st kickoff meeting at Somerville’s Old Post Office in Union Square. “Cities are for people” and design decisions should focus on “happiness and well-being,” he said.

Under the progressive leadership of Somerville Mayor Joseph Curtatone, the city hired Gehl Studios as part of their Somerville by Design initiative to reimagine the city’s environs, part of an ambitious agenda to build more housing, increase access to green space and improve the quality of public life. To figure out how people use existing space, Gehl’s team merges two disciplines: social science (tracking how people move about in urban areas) and design (form), and recruits dozens of local volunteers to take part in gathering the real-time community data.

“In Somerville, 32% of the assets are streets. Who do you want to invite to use them? How do you want others to use the space?” Risom says. “Many people know how cars move; very few know how people move,” he said. “Information about how people use space [should] inform design decisions.” Workshop attendees provided some of their own data by marking-up maps of Somerville with favorite spaces, posting sticky notes with the qualities of their best-loved spots, and color-coding areas on the map that need improvement.

Later in May, the Gehl Studio team, working with Somerville’s planning department, will send observers into the field to find out how long people stay in a public space, whether all ages use the area, and if families take advantage of some places but avoid others. This feedback is key to understanding what people in a city need and where thoughtful planning can intervene.

Certain universal concepts have emerged from Gehl’s previous data collection in Copenhagen and other cities around the world. For example, people everywhere seek protection when outside (safe environment), comfort (in sun, shade and various weather conditions) and enjoyment (connection to other people, seating, places to talk and to be part of a network).

Ghel’s data collection results show that people don’t behave like computers or designers often expect. People move in a way they deem most comfortable, and they need continual stimulus.

People walk about three miles per hour, but their perception of the time it takes to walk anywhere varies depending on the extent of stimulus. We need one stimulus every four seconds, says Risom, and this helps explain why walking seems faster and more pleasurable when we can scan fresh fruit at the farmer’s market, smell the roses at the florist, admire the sparkling lights in the shop window or listen to a street band on the way to a train station.

Our trips are happier when we can find shade in summer and sunshine in winter. When congregating in a public place, we tend to spread out if possible, somewhere between 10 and 20 feet until we want to socialize, then we prefer three to six feet.

Detailed behavioral data collection in Somerville begins next month because it’s important each place be true to itself, Risom explains. The point is not to turn Somerville into Copenhagen, but to make Somerville the best it can be—as well as raise expectations about how a city can look and feel. “

At the end of May, an army of researchers [students and citizen volunteers]” will canvas the city with surveys to obtain more data, Brad Rawson from the City of Somerville Planning office explained. Gehl Studio designers will train those ‘Public Space, Public Life Survey’ volunteers on May 27 for the data gathering to take place on Thursday, May 28 and Saturday, May 30.

Volunteers will ask questions such as, “Where in Somerville needs more love? What qualities define your favorite space? Which public spaces do you use daily? What are the characteristics that make your favorite place feel, smell, sound or look good? Which public spaces need improvement?”

Want to spread the word? You can learn how to here: http://www.somervillema.gov/news/world-renowned-firm-hired-address-public-space-challenge

Then everyone will want to know who will be the next ‘Somerville’? (Or one down, 350 more to go!; there are 351 cities and towns in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.)

By Janice M. Ward and Ann Sussman